Framing Statement

Fear of Fantasy was an installation based piece that took place in the Great Central Library’s Worth Room. The piece was performed by Jessica Bark, Ruth Scott and I on the 7th May 2015. The set up of the installation process began at 8am and was completed by 12pm, with performances starting at 12:30pm and lasting until 7:30pm. The get out process to transform the Worth Room back to normal was completed by 10:30pm that night.

Upon initial examination of the University of Lincoln’s library as a performance site, we started to explore the reasons as to why people used it. Predominately, the university library is used by students and staff as a place of learning, to conduct research and write assignments. This was interesting to us as typically libraries are thought to be places that shelve vast amounts of fiction for users to enjoy and get lost in. The Great Central Library itself houses a large collection of fictional books that are not read for their intended purpose of pleasure. The fictional books in the university library are primarily used for in-depth analysis, and the world that the authors create is usually ripped apart by students in essays and exams. For a library that is home to so much fictional work, it seemed a shame to us that these dramatic worlds that writers create are not being explored intently by library users.

With this in mind we were drawn to the idea of visually exploring the worlds narratives exposed as a form of installation. This would enable library users that don’t have time to read for pleasure whilst struggling with university assignments a chance to get lost within the world of the fiction that inhabits a large proportion of the books in the library. This also led us to explore what the library meant for its users, and found it be a catalyst into adulthood. Students spend a lot of time in the library building a future for themselves by the means of the hard work it takes to achieve a university degree. Through this transitioning stage into adulthood that students undergo whilst at university, we were able to draw parallels with the themes of childhood innocence and adulthood found in the fictional work of Grimm’s Fairy Tales.

The fantasy world created in the Grimm tales was something that had the potential to inspire a visually appealing installation piece, which we thought would make our student audience want to take time out of their studies to explore. Three of the fairy tales we were drawn to most that dealt with the loss of childhood innocence were Ashputtel, The Girl With No Hands and Snow White. We thought that by using the world of fantasy as a basis for our installation, we would be able to successfully portray the fictional brought to life. The combination of why people used the library, the effect that the library had on changing adolescence and the magical potential of fairy tales is what led us to create our installation, Fear of Fantasy.

Analysis of Process

Theatre and Architecture:

When exploring the possibilities of performance that the Great Central Library had to offer, it became evident that each space would denote different performance outcomes. Rufford states that: “Architecture articulates space, giving it a particular feel. Staging a performance is about acting in architecture: it is a practise that demands we pay attention to distance, scale, style, person-to-volume ratio and the immaterial architectures of light, heat and sound.” (Rufford, 2015, 3-4)

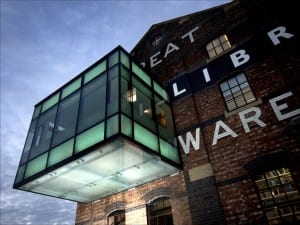

We came across the Worth Room, a small group workroom, located on the second floor of the library. This space was instantly appealing as it is a new part of the building that had been specifically added on to the architecture of the building, making it stand out structurally.

The visually appealing aesthetic of the Worth Room, as seen from the picture above, enticed us to want to use it as a performance space. As the small room is largely hidden from the viewpoint of somebody inside of the actual library the idea to make an installation piece inside the Worth Room that symbolised a fantastical ‘secret escape’ was created. Another thing that attracted us towards the idea of creating an installation-based piece was the structural feature of the window looking into the Worth Room. From the inside of the library, the window seemed to lend itself to the idea of people being able to look in at a magical environment that would be created in the library.

The picture above denotes the view of the library through the window of the Worth Room, which creates a notion of ‘looking in’ on something fantastical. We believe this notion provided something darker that we wanted to explore further. This led us to produce a sinister element to our material in relation to the loss of childhood innocence in fairy tales that would interlink with the notion of students losing their childhood adolescence whilst at university.

Installation Art:

Due to the nature of the Worth Room, we wanted to create a space that felt immersive in fantasy and fiction, and thought that an installation of this world would bring the narratives to life. “Installation art is a term that loosely refers to the type of art into which the viewer physically enters, and which is often described as ‘theatrical’, ‘immersive’ or ‘experimential’.” (Bishop, 2012, 6) We wanted our installation to appear authentic and give viewers the impression that fantasy fiction had been brought to life in front of them.

To achieve this aim we explored how installations could have the potential to make viewers feel fully immersed in the environment. Bishop states that installation art: “addresses the viewer directly as a literal presence in the space. Rather than imagining the viewer as a pair of disembodied eyes that survey the work from a distance, installation art presupposed an embodied viewer whose senses of touch, smell and sound are as heightened as their sense of vision.” (Bishop, 2012, 6)

Using this quote we were inspired to make the installation as immersive as possible for the viewer. We began to create mood boards of ideas surrounding what we could include in our installation. This was helpful as we were able to get a visual sense of the scope of the project and the kind of supplies we would need to execute it.

We decided to incorporate Bishop’s idea of the viewer using all their senses in our installation. We thought to use real ivy, which was cut fresh from Jess’ house a few days prior to the performance day, to decorate the walls of the Worth Room in order to produce a genuine, earthy smell that would help represent a fantastical forest.

Exploring fairy tale installations, we came across the work of Jennifer Crighton. Her work on fairy tale installations, as seen in the picture below, seems to explore the sinister element attachted to Grimm’s tales. Exploring this sinister notion within fairy tales, we came up with the idea of ‘time running out’ as a way to frame our piece, which underscored it with an unnerving atmosphere. This linked to the loss of innocence within the tales and how time runs out on a student’s childhood whilst at university, which provided greater depth to the immersive element of the piece, as the audience would feel that because there is limited time, they are put under greater pressure to succeed.

We also decided through this that we wanted a soundscape to play, through a speaker, throughout the viewer’s time experiencing our installation. This would add to the ambience of the installation, and we experimented with numerous different types of fantasy music. We wanted the music to provide a sense of the sinister side of fairy tales, highlighting the potential fear created by the idea of lost innocence. Using Audacity, I created a fifteen-minute soundscape that used a mixture of sweet sounding and sinister musical interludes as well as a recorded piece of narration centred on the initial concept of our piece. This is available on Soundcloud through the following link: https://soundcloud.com/harrywalsh95/fear-of-fantasy and through the widget below.

I recorded and distorted Jess’ narration, which acted as a guide to the audience members. “Open your eyes, pull back the sheet, there are characters here that you need to meet. Dear Ashputtel, a girl and a queen, there is importance in fantasy stories, let us see what they mean. Don’t run or hide or scream or shout, enjoy this story before the time runs out.” (Bark, 2015) The illusion to time running out helped create a sense of fear and worry, and I used voice distortion tools on Audacity to emphasise the unnerving nature of this.

Bruno Bettelheim and The Uses of Enchantment:

After realising that we wanted to explore the idea of a fantasy and fairy tale installation within our piece, we looked to the work of Bruno Bettelheim. In Bettelheim’s book, The Uses of Enchantment, he states that fairy tales get across the message to children that: “struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable, it is an intrinsic part of human existence – but that if one does not shy away, but steadfastly meets unexpected and often unjust hardships, one masters all obstacles and at the end emerges victorious.” (Bettelheim, 1978, 8) This particular quote highlighted the parallels between what users in the library go through to get their degrees and the message of fairy tale fiction.

We started investigating the notions of ‘struggle’, ‘hardships’ and ‘obstacles’ because of this and found links between the original usage of the Great Central Library as a grain warehouse and the imagery of grain in Grimm’s tales. In the story of Ashputtel, the title character is forced by her stepmother to separate a mixture of grain and ash in order to go to the ball. This image of manual labour related both to the original historic use of our performance space and the notion of students working hard. Due to this, we were then inspired to make our piece centred on audience interaction using forms of manual labour involving grain.

The audience were to be asked if they would help Ruth, who was playing the character of Ashputtel, to separate the glitter and the grain as seen in the photo above. By having the audience contribute to this task, we wanted to emulate Bettelheim’s ideas of facing hardships and obstacles and being able to overcome them with adversity, as fairy tales represent.

To allow audiences to feel fully immersed in the fairy tale environment in such a small room as the Worth Room, especially whilst actively being involved within the piece, we explored the possibility of one-to-one performance within our installation.

One to One Performance:

“One to One performance foregrounds subjective personal narratives that define – and seek to redefine – who we are, what we believe and how we act and re-act. In One to One we are lifted out of the passive role of audience member and re-positioned into an activated state of witness or collaborator, or more subtly energized into ‘acting’ voyeur.” (Zerihan, 2006) The idea of audiences as active contributors to a performance is something that intrigued us. This seemed to compliment our idea of having the audience take part in tasks involving grain.

Due to this, we decided One to One performance would be a more effective way to immerse the audience and create a sense that they were an integral part of the piece.

After deciding this, we began to explore ways of making the performance immersive for the single audience members. “One to One performance affords the spectator to immerse themselves in the performance framework set out by the practitioner. This can be a seductive / scary / liberating / boring / intimate prospect and an even more intensive experience.” (Zerihan et al, 2009) From exploring the sinister notion in the Grimm’s tales, we thought it would create an intense experience for the viewer.

To create this feel, we experimented with different ways of interacting with the audience member. In relating to the childlike innocence in fairy tales, we explored the idea of having the individual have to lay down in a make shift bed, emulating ‘story time’. We tested this idea on a group of students, and had them lay down in the worth room on a duvet. The students claimed they felt uncomfortable and unnerved the longer they had to lay down, which was the desired effect. One of the students we tested this one stated: “It felt weird, it felt like something was going to happen! I was on egde.” (Hill, 2015)

Pictured above is the concept of bed in its fully realised state at the day of the performance. The level of detail in the installation helped to create a greater sense of immersion, and for audience members to engage with the environment on a direct level.

Performance Evaluation

Prior to setting up our installation we arranged timetabled performance slots using a Doodle Poll that was advertised through a Facebook event page. These performance slots were half an hour in length, providing us enough time to reset before the next audience member would enter. The slots ran from 12:00pm to 7:30pm and were fully booked a day before the piece went ahead. We performed 15 times throughout the day to solo audience members.

One audience member commented: “Just been into see your Site-Specific piece (I hope I left at the right time!) I just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed it. I went to see Grimm Tales in London a few weeks ago and it reminded me very much of that.” (Jones, 2015) Many other audience members that took part in the piece shared positive reviews of the piece on the Fear Of Fantasy Facebook event page, as detailed in the photo below.

Throughout the process of continuous performance the nature of our piece changed and developed as each audience member stepped into our installation. With this in mind, the performances towards the later end of the day appeared stronger than the initial ones. The earlier performances lasted around seven minutes on average, with the later ones lasting around fifteen minutes each. This development came around as we found that we wanted to allow the audience members more time to engage with the environment that we had spent time creating in depth.

These images detail our installation after it’s completion. In spending a lengthy amount of time in the environment when it was complete, we began to truly appreciate the environment that we created as a piece of performance in its own right. We felt like our audience should have a larger opportunity to appreciate this too. This triggered the decision to allow audience members a much longer time to explore the environment before we began interacting with them directly. This allowed for a more immersive installation experience for the later audience members.

It was beneficial to us to have the opportunity throughout our piece to perform multiple times, as we were finding ourselves constantly reacting to the space in unique ways for each audience member. For example, one audience member at the beginning of the process was very keen to explore the environment of the installation, leading us to the decision to adapt the way we interacted with them. Due to the audience members level of immersion within the installation, we decided to act less manic and much more subdued in our interaction. We felt this was more effective in terms of a one-to-one performance, and the audience member was able to get much more of the feeling of fantastical exploration of what we desired.

From spending the entire day in the environment of our created installation, I began to appreciate the potential that installation spaces had as stand-alone performance pieces. If I were to alter the performance in the future I would focus even more time and effort into creating an environment for all audiences to truly be able to have fun exploring and getting lost in. By doing this we would be able to further achieve the goal to allow audiences to submerse themselves within the world of fiction while at the Great Central Library.

Word Count: 2704

Bibliography

Bettelheim, B. (1978) The Uses of Enchantment. London: Penguin Books.

Bishop, C. (2012) Installation Art. London: Tate Publishing.

Hill, C. (2015) Questions on testing the space. [interview] Interviewed by Harry Walsh, 1 May.

Jones, K. (2015) Site. [email] Sent to Harry Walsh, 7 May.

She Paints Red, (2013) Phantom Wing. [online] Available from: https://shepaintsred.wordpress.com/2013/09/27/phantom-wing/ [Accessed 24 March]

Rufford, J. (2015) Theatre and Architecture. London: Palgrave.

Zerihan, R. et al (2009) Live Art Development Agency Study Room Guide on One to One Performance.

Zerihan, R. (2006) Intimate Inter-actions: Returning to the Body in One to One Performance. [online] Available from http://people.brunel.ac.uk/bst/vol0601/rachelzerihan/home.html [Accessed 8 May 2015].