09193711

3209 words.

Framing Statement

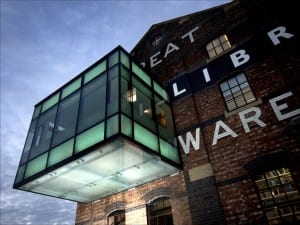

Fear of Fantasy was an installation based piece, performed on the 7th of May 2015 in The Worth Room of the Great Central Library, a part of the University of Lincoln. The installation took four and half hours to set up, with performances starting from 12:30pm until 19:30pm, followed by a break down until 10:30pm. The piece was performed by Harry Walsh, Ruth Scott and I.

Upon examination of The Great Central Library as a site, we began researching the variety of reasons people might use it. The library’s catalogue can be split into two categories; facts and fiction. We could determine that the library is mainly used by staff and students for research, essays, revision and assignments, therefore facts. Although the library houses a wide selection of fictional books, we found that these books are rarely used for enjoyment, but more so used in analysis for essays and projects.

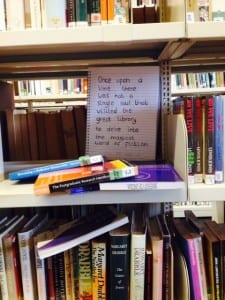

We began to consider the library as a ‘catalyst’ into adulthood, whereby students use the space in order to prepare themselves, through education, for adult working life. Therefore we made the decision to create a piece that promoted fiction for enjoyment, with particular emphasis on fantasy and fairy-tales. We chose fairy-tales because they are associated with adolescence, and so by re-creating this we hoped to promote the child-like enjoyment of fiction and reading. However, in order to make this appropriate to adults, there were several things we had to consider. We were aware that many students do not have time to enjoy fiction, with the pressure of deadlines and exams dictating which books they must read. We also knew that we couldn’t use typical children’s fairy-tales, as these are not often appealing to adult readerships.

So we decided to create an installation piece, giving students the opportunity to physically immerse themselves into a ‘world of fiction’ so that they could literally get ‘lost within it.’ By using an installation framework, students could experience fiction, but in a short-time span compared to reading a book. The decision was made that the installation would be highly materialistic, with several components creating a ‘fantasy word.’ For example, objects, sounds and smells that are associated with the fantasy genre. We chose to black out the windows, so that the Worth Room would be unrecognizable, we decorated each wall with real ivy, fantasy books, origami flowers made from pages of books and fairy lights. In addition, to make the piece ‘come to life’ we decided that we would all take on characters from fairy-tales and ask our participants to become a part of the action by helping us with tasks. In order to make the fairy-tales appealing, we decided to use Grimm’s Fairytale’s as our fictional influence, in the past, were considered as too “violently descriptive for children” (Grimm, 1999, xi). Therefore more appropriate for our adult participants.

Reading a book is something a person does alone. Therefore, we made the decision to make our piece a ‘one-to-one’ performance, whereby only one participant could enter the installation space at a time.

Analysis

First Idea

In class, we were given the task to create an ‘Art Book,’ titled from an earlier exercise we had done. The previous exercise was to ‘just write’ book titles, without thinking. I noticed that the majority of my title could be classed within the ‘fantasy genre.’ Therefore, I chose the title “Facts and Fairy-tales.” I knew that finding the time to get lost within a fictional story is rare, and that this was the case with many university students. We often only find ourselves reading in order to gain factual knowledge. I realised that the only time I really get lost in a story is when I’m asleep and dreaming. Therefore I decided to create a book of fairy-tales. Fairy-tales have importance because their totally unrealistic nature is a mode of escapism from the pressures of University. Furthermore a Fairy-tale is not attached to a specific site. But it had to be appealing to students. Grimm’s Fairy-tales, first published in 1812 were banned for being too violently descriptive and frightening for children. Perfect, however for people aged 18 upwards. I decided my book should predominantly be of pictures and only include short snippets of fantasy text – therefore being visually stimulating.

Keeping in mind my idea of dreams, I decided my book should take on the form of a baby mobile. I used string, burnt paper and dead flowers to further enhance the visual imagery. This idea behind this ‘Art Book’ was that it could influence a person’s dream state; thus allowing them to get lost in a fairy-tale world.

Fear of Fantasy is an idea discussed by Bruno Bettelheim. The idea that children are sometimes neglected from fairy-tales and fantasy because they do not offer representations of reality.

“Some people claim that fairy tales do not render ‘truthful’ pictures of life as it is, and are therefore unhealthy” (Bettelheim, 1978, 116).

We realized we could apply this theory to the students of the University, who rarely use the library for fiction reading because it is ‘unhealthy’ to their study. Rather we believe that students only used] the library for factual research. The University library has a large selection of fictional books, so we began to wonder why students might not utilize the space for this purpose. One reason stood out.

Deadlines and exams dictate how students use their time in the library.

However, before we could go ahead with a project – we had to ensure that our theory was true.

We conducted a ‘visual survey’ in order to determine how many students use to library for fiction.

We found that only 2 out of 18 people who engaged with survey have ever used the library for fictional reading. As a result of these findings, we decided to continue with the idea of presenting fairy tales. The choice was made that our main aim would be to promote the library as a place to enjoy fiction.

Further developing the ‘Art Book’ our group began to think how we could expand this idea of making a Fairy-tale a ‘visual’ experience. Something that could be enjoyed in a shorter amount of time than physically reading. We made a mood board to demonstrate how a book could become a visual experience. Using different materials, images and lots of glitter it led us to our performance idea.

![photo_4[1]](https://sitespecific2015dhu.blogs.lincoln.ac.uk/files/2015/03/photo_411-300x195.jpg)

We felt the best choice would be the use of Installation Art.

In our initial pitch, we hoped to transform a large section of the second floor. Our idea was to ‘install’ fairy tale props, attached to ivy which would lead to an installation room. However, taking on board comments from our tutors we decided it was better to just go ahead with a room installation.

We felt this would emphasise the effect of ‘walking into another world’ so that people could ‘literally get lost within fiction.’

Theatre and Architecture

“Staging a performance is about acting in architecture: it is a practice that demands we pay attention to distance, scale, style, person to volume ratio and the immaterial architectures of light, heat and sound” (Rufford, 2015, 3-4).

Fairy tales are not often associated with a specific site, especially not in a library. But in order to make our piece effective, we knew we had to use a space which promoted the idea of ‘another world.’

Reading Rufford’s Theatre & Architecture allowed us to apply the possibilities for different contexts to specific spaces. By looking at architectural physicality of certain areas, we could determine if they would be appropriate to house an installation.

The Worth Room of the library displayed excellent qualities to exhibit an installation.

As a modern addition to the library, it holds different meaning to the rest of the building. The library building was previously used as a grain warehouse. The Worth Room, however was added specifically to cater to the needs of study. The interior of the room features three glass walls, looking directly outside. We felt this could be interesting to build an installation piece on, as we could ‘block out the outside world.’ The outside world being a metaphor for ‘reality.’ One main aspect of the architecture we felt would be beneficial to our project was the inside window.

This window would mean that anybody passing by could become an audience member by looking in at the installation.

In terms of the dimensions of the room, we felt it was a good size in order to create the installation. Designed to be an intimate study room for small group meetings, it meant it could also be utilised as an intimate performance space.

The Installation

Bishop states that Installation Art should be something that the viewer “physically enters” (Bishop, 2012, 6). It should be “theatrical”(ibid), “immersive”(ibid) or “experimental” (ibid).

In regard to viewers ‘physically entering’ a space to experience art, this was perfect if we were to achieve our goal of participants entering a world of fiction. However to make the ‘world’ seem realistic, we also took on characteristics of immersion art. Immersion means creating “the convincing depiction of detailed reality” (Dixon, 2007 128).

In order to achieve this, we knew that the installation had to be highly materialistic in order to create a world that totally transformed The Worth Room, giving the space a different meaning.

We installed several layers of objects into the room in order to create this world,with the intention to stimulate four out of five of the human senses; sight, smell, feel and hearing. This decision came after reading that “immersion can relate to experiences that are both mental and physical” (Dixon, 2007, 127). By appealing to these senses, we could appeal to both mental and physical aspects of our participants.

We began by blacking out all of the windows, except the internal one, thus removing any influence from outside of the space. We made hundreds of origami, felt and netted flowers to drape around the room.

We used many other objects such as fantasy books, feathers, bird-cages, rose-plants, mirrors, grain, fake blood, glitter, different coloured nets, and so on. Vast amounts of ivy were used in order to cover the entirety of the space. We used fairy-lights, and covered the built-in lights with green gels in order to make the light of the room gloomy.

This ensured we had many layers of visually interesting objects, in order to stimulate the participant’s sight. The benefit of the many layers of visual stimulus meant that passers-by could also become an audience by looking through the window at the transformation.

Another benefit of the ivy was the smell it gave to the room. This scent was locked in, and participants only experienced it upon entrance. Therefore this stimulated the participant’s sense of smell.

We created a soundscape. A collaboration of fantasy sounds; birds, harp-song and a light piano tune with the addition of a narrative ‘story-teller’ as the track progressed meant that the participant’s sense of hearing was also enthused.

Soundscape: [https://soundcloud.com/harrywalsh95]

In order to fulfil the sense of touch, we firstly invited our participants to explore the space, whereby they were allowed to pick up books, objects and touch the surroundings. A main aspect of the installation, however, was the implantation of a bed in the centre of the room.

Going back to Bishop’s guidelines of Installation Art, we decided that the ‘theatrical’ element to our piece could be intensified by us taking on characters of Grimm’s fairy tales and using them to conduct one to one performance. Within these performance’s we hoped to fulfil the sense of touch.

One to one performance

We developed our understanding of one to one performance through Zerihan’s definition of it being “the inter-relationship between performer and spectator” (Zerihan, 2006, 2). Furthermore we understood its function as “subjective personal narratives that define – and seek to redefine – who we are, what we believe and how we act and re-act” (Zerihan, 2006, 1). By placing participants into a ‘different world’ we hoped that it would affect their behaviour. When conducting research, we performed ‘mock’ runs to participants. One stated that “when I entered into a space where people were already acting, I felt like I had to act as well. I felt a bit vulnerable!” (Hill, 2015). Furthermore we wanted our participants to react to the performance tasks which the fairy tale characters set. These tasks functioned in order to build a relationship, making them move involved, between participant and performer. By building this relationship, we hoped that

For example, the first task was telling the participant to “get into bed.” Some did so willingly, but others questioned why. It meant that not only did the participant react to the nature of the performance, but the performer also had to react to the changing behaviours of each participant.

Other tasks used sense of touch as a foreground.

The character of Ashputtel insisted that the participant must help her “separate the grain from the ash” so that she could “go to the ball.” By asking participants to physically engage with the performer, we hoped it would make the surroundings more ‘real’ – thus successfully creating immersion. Touch was further used when the participant moved onto the next performer – The Girl With No Hands. The participant was told to wash their hands in a bucket of soapy water, their hands touching the performers.

The final one to one performance was with The Queen character, who, standing behind the participant with arms reached around them held a mirror up to their face. The participant was asked to pick out their faults. By letting the participant see their reflection in the mirror within the installation we hoped it would make the realisation of, as Zerihan describes “who they are” within the space.

Each character involved in the one-to-one performances were drawn from Grimm’s Fairy-tales. We did a lot of research into Ashputtel, The Girl With No Hands and Snow White. We discovered that these three stories, as Bettelheim has argued about fairy tales, allow readers to “understand the complex world in which we need to cope” (Bettelheim, 1978, 5). All three fairy tales display a story about vulnerability, and how to overcome obstacles. Highly relevant to a student target audience, as University faces us with several obstacles which we must overcome.

We felt the use of one to one performance was highly relevant when re-creating the experience of ‘getting lost within fiction.’ We base this on the fact that reading is a solo activity, therefore the experience of Fear of Fantasy should also be an individual engagement.

Characterisation

The costuming and make-up of our characters was highly influenced by Carnesky’s Ghost Train.

Carnesky makes use of fictional ‘ghost’ characters in order to “breach the gap between art and entertainment” (carnesky.com, 2015).

In the same way we wanted to do so with our piece, removing the gap between the installation and the performance. Therefore our characters embodied similar materiality to the surroundings. Ashputtel, in a dishevelled, ash-stained dress with black bags under her eyes displayed a fairy tale character highly relevant to the violent imagery in Grimm’s Tales. In addition, The Queen wore several layers of make up in order to display the “harsh vanity” (Grimm, 1992, 5) of the Snow White Story.

By placing one to one performance into installation art, it was our aim to immerse participants, based on their mental and physical senses into a fantasy world whereby they could enjoy the fiction being displayed in a shorter time than reading a book.

Evaluation

Due the one to one performance nature of our piece, we created appointment slots on a Doodle Poll which was advertised on a Facebook event page.

There were 15 slots available, starting from 12:30pm until 19:30pm. All 15 slots were filled by the day of the performance, and we had an additional two participants who walked in of their own accord. We also found that our installation catered to an audience of passers-by, who were intrigued to see the transformed space.

The reactions we received to Fear of Fantasy varied dramatically from person to person. Our research led us to believe that by creating an installation, participants would look around the environment upon entering the room. However with the addition of character’s in the room, ready to engage in one to one performance, we discovered that participants were reluctant to do so, due to feeling uncomfortable. Therefore after this realisation, we began inviting participants upon entry to “look around.”

In regard to the tasks set out for the audiences, we also found that the longer we made them partake in these, the more immersed they felt within the action and the bigger the reaction we would receive at the ending. We discovered that by starting the action slow, building the tension at a steady pace, it meant the end reaction was greater. We seemed to lack the escalation of tension in the earlier performances, but starting the one to one performances too quickly, and not allowing participants to enjoy the space. Once we slowed the pace down, with performances lasting around 15 minutes as opposed to 7 minutes, participants left the room with a far bigger reaction; some scared, some laughing and some just shocked.

The intricacies of the installation worked well. The layers of visual imagery completely transformed The Worth Room to an unrecognisable place. “I couldn’t believe that this was a study room I was revising in yesterday! I didn’t recognise it” (Maskill, 2015). Furthermore we catered to a far bigger audience than just the 15 participants. Many people came up to look through the window at the transformed space, examining each detail. I think the installation worked well because it removed the meaning from the space, and instead prescribed it something different. Instead of holding the meaning of ‘studying’ the site became a place that could be seen as a fairy tale land.

If improvements were to be made on the final performance, I would like to immerse participants within the action for longer. The intricacies and characterisations weren’t allowed enough time to fully be appreciated. I felt that had the appointments been an hour long, then we could have experimented further with how long we could engage each participant based on their reactions – as some really did not seem to want to leave!

Furthermore, if I were to alter the piece, I would like to experiment with this idea just as an installation piece, removing the one to one performance and focusing even more on the idea of transforming space and prescribing it a new meaning. I feel then audience members could spend as long as they want enjoying the performance.

This module has heightened my awareness of how a specific site can hold meaning, but also that we can change that meaning. It allows us to experiment with performance that the constraints of the theatre do not. The theatre has a set space, which dictates audience to performer. As I have experienced through one to one performance and immersion, site specific performance allows us to create reactions from audiences based on the individual’s mentality.

Bibliography

Bettelheim, B. (1978) The Uses of Enchantment. London: Penguin Books.

Bishop, C. (2012) Installation Art. London: Tate Publishing.

Carnesky, J. (2015) Carnesky’s Ghost Train. [online] Blackpool: Blackpool Visitors Guide. Available from http://carnesky.com/ghosttrain/ [Accessed 15th May 2015].

Dixon, S. (2007) Digital Performance. A History of New Media In Theatre, Dance, Art and Installation. Cambridge: MIT press.

Hill, C. (2015) Questions on testing the space. [interview] Interviewed by Harry Walsh, 1 May.

Jones, K. (2015) Site. [email] Sent to Harry Walsh, 7 May.

Maskill, H. (2015) Questions on testing the space. [interview] Interviewed by Jessica Bark, 1 May.

She Paints Red, (2013) Phantom Wing. [online] Available from: https://shepaintsred.wordpress.com/2013/09/27/phantom-wing/ [Accessed 24 March]

Rufford, J. (2015) Theatre and Architecture. London: Palgrave.

Zerihan, R. et al (2009) Live Art Development Agency Study Room Guide on One to One Performance.

Zerihan, R. (2006) Intimate Inter-actions: Returning to the Body in One to One Performance. [online] Available from http://people.brunel.ac.uk/bst/vol0601/rachelzerihan/home.html [Accessed 8 May 2015].